A recent opinion piece in our local newspaper argued that “one word more than any other explains why New Mexico has not grown or prospered as much as neighboring states … corruption.”

Meanwhile in a Continuing Ed class at Santa Fe Community College we learned about the dealings of the so-called Santa Fe Ring, which dominated New Mexican politics in the 1880s.

Now we already knew a thing or two about corrupt politicians having spent the first 74 years of our lives in Connecticut, once dubbed “Corrupticut” by the New York Times. Among other things e.g. in July 2004, the state’s governor resigned from office amid a corruption investigation, then served ten months at “Club Fed.” Around the same time, but unrelated, the mayors of four of the state’s biggest cities were similarly indicted and convicted. For one city it was the third consecutive mayor to be so charged.

The New Mexico corruptions mentioned in the op-ed piece all occurred since we moved here. But, like CT, there were others.

“From 1995 until early 2024, law enforcement officers in Bernalillo County accepted bribes to torpedo drunken-driving cases … the bribed cops [did not] appear in court for DWI cases, an efficient means of obtaining dismissals.

“[The] former Democratic floor leader of the state House of Representatives [resigned] amid allegations she stole [millions of dollars] from her then-employer, Albuquerque Public Schools.”

A former Secretary of State “doctored campaign finance records to steal contributions to feed her gambling habit.”

Connecticut’s corruption is of the classic vanilla variety – bribes, payoffs, free home improvements, etc. whereas New Mexico’s seems to show more originality, but with an equally impressive display of hutzpah. Makes sense – CT is after all “the land of steady habits,” while NM’s motto is Crescit Eundo or, translated from Latin “It Grows As It Goes.” Neither sets of behavior are scandalous enough however to displace either Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Alabama, Alaska, South Dakota, Kentucky or Florida in the National Law Review’s list of the Top Ten most corrupt states. (The least corrupt states are Washington and Oregon.)

And none of this malfeasance comes close to matching the audacity, dishonesty and deleterious effects of the Santa Fe Ring, referred to by historian Victor Westphall as “the most corrupt combination that ever cursed any country or community … It has vilified, oppressed or otherwise sought to ruin every man who had the independence and hardihood to oppose its corrupt schemes.”

Land grants were made to individuals and communities during the Spanish (1598-1821) and Mexican (1821-1846) periods of New Mexico’s history – private grants to individuals, and communal grants made to groups of individuals for the purpose of establishing settlements as well as to Pueblos for the lands they inhabited.

“In 1846 the United States began its occupation of New Mexico, and in 1848 the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo established New Mexico as part of the United States. Article 8 of the treaty stated that ‘property of every kind now belonging to Mexicans not established there shall be inviolably respected.’” (New Mexico State Records Center and Archives)

Article 10 of the treaty further guaranteed the protection of Mexican land grants and property rights in the territories ceded to the United States, but was removed by the U.S. Senate during ratification.

However, the treaty lacked clear-cut procedures for confirming these grants. So “in 1854 the U.S. government established the office of the Surveyor General of New Mexico to ascertain ‘the origin, nature, character, and extent to all claims to lands under the laws, usages, and customs of Spain and Mexico.’”

However documentation of the properties was often vague as to sizes and boundaries, and record-keeping erratic or non-existent. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 destroyed nearly all of the Spanish documents in New Mexico at that time. Later more were carelessly thrown away by some Spanish/Mexican governors.

In addition, most Hispanic claimants of the land did not speak much English and/or understand the American legal system. Many were poor and unable to pursue the lengthy and costly legal process Moreover, the Surveyors General had little knowledge of Hispanic land practices and customs.

A few of the small number of lawyers in New Mexico realized “that a fortune lay in the legal process of quieting [obtaining] title to the disputed Spanish and Mexican land grants. Or, if not that, in securing for themselves or clients control of these lands for the purpose of speculation.” (Howard R. Lamar, Utah Historical Quarterly) This group of influential Anglos and a few Hispanos, became known informally as “The Santa Fe Ring.”

Facilitated by U.S. courts who had no allegiance to New Mexican claims, members of the Ring used their political connections, legal expertise, and financial resources to manipulate the system and gain control of vast tracts of land originally belonging to Hispanic landowners and others, which they then would repackage and sell at an inflated value. As a result, “large grants owned by speculators were erroneously confirmed; other grants which should have been confirmed were not [and] some valid grants were confirmed, but to the wrong people.’ (Placido Gomez, Natural Resources Journal)

But New Mexico being part of the “wild, wild west” it did not take long for all this chicanery to spill beyond the walls of the courtroom into public view.

The Maxwell Land Grant was a nearly two-million-acre property in northeastern New Mexico, originally awarded to Charles Beaubien and Guadalupe Miranda in 1841 by the Mexican government. Lucien Maxwell married Beaubien’s daughter and became a part-owner and manager of the vast land grant. He bought out the other owners over time, and over the years tacitly allowed numerous farmers and miners to settle and work on the land. The Ring acquired a share of the grant and aggressively marketed it to investors, often exaggerating its potential for agriculture, grazing, and even gold mining before selling it to a Dutch Firm in 1872 who decided to clear out all of the “squatters.”

The longtime homesteaders objected to being pushed out by the new owner. The Ring got involved and hired gunslingers to force off the outnumbered and outgunned habitants. Reverend Franklin J. Tolby, a Methodist minister, sided with the settlers making public statements on their behalf and sending a series of letters to the New York Sun exposing the Ring’s corrupt methods. In 1875, the clergyman was shot and killed. Rumors started that the local constable Cruz Vega, was involved. A pro-settler mob confronted Vega and hanged him by the neck from a telegraph pole. Before dying Vega implicated two members of the Ring who barely escaped capture by the crowd. Over 200 deaths later what by then had become known as the “Colfax County War” ended in 1887 when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Dutch Land Grant Company, which continued its exploitation of the many resources and thrived for several decades.

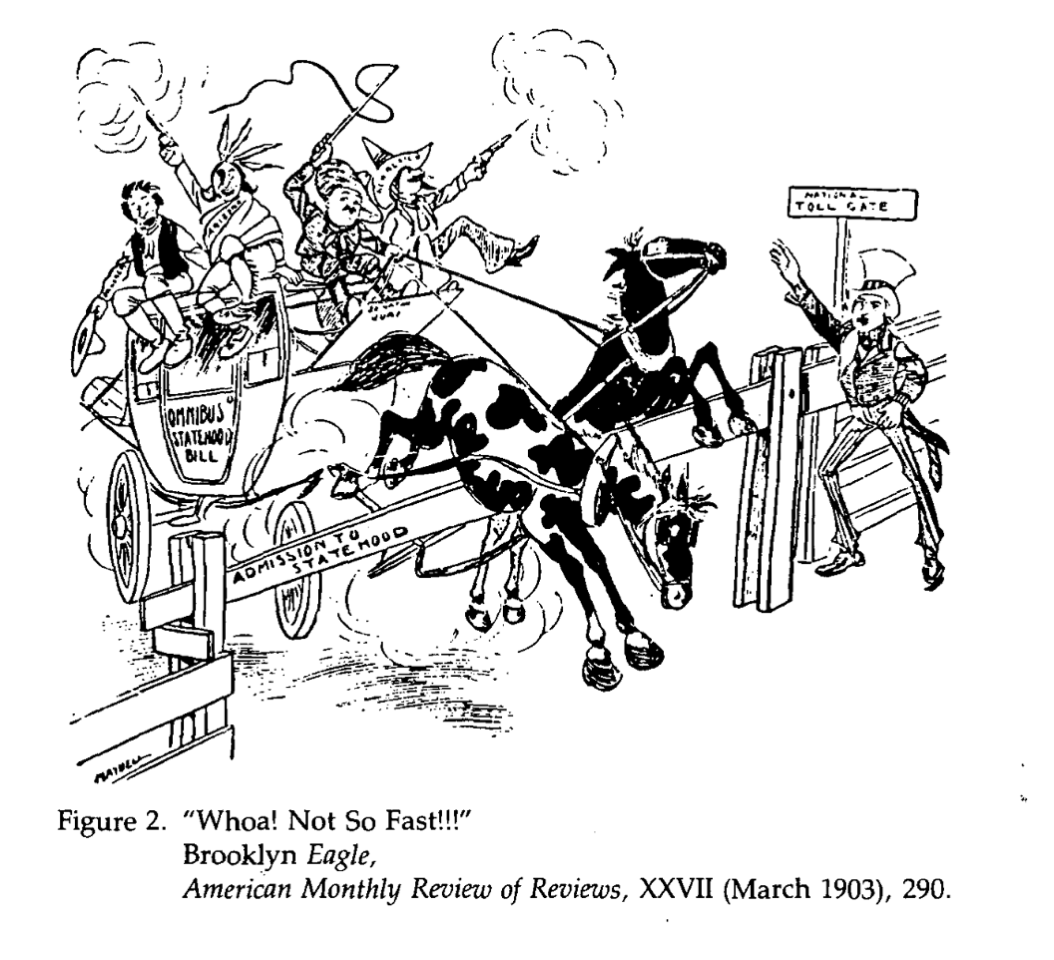

(A 1903 “omnibus” bill to admit Oklahoma, Arizona and New Mexico into the Union was one of many such attempts that failed in the U.S. Senate.)

Although the Santa Fe Ring had many allies and associates in the federal government and courts the territory’s “wild, wild west” reputation amplified by the Colfax conflict and another in Lincoln County, along with Anglo-Protestant prejudice against Spanish-speaking, Roman Catholic Hispanos, language barriers, and concerns about the territory’s economic viability contributed to the delay of New Mexico becoming a U.S. state until 1912.

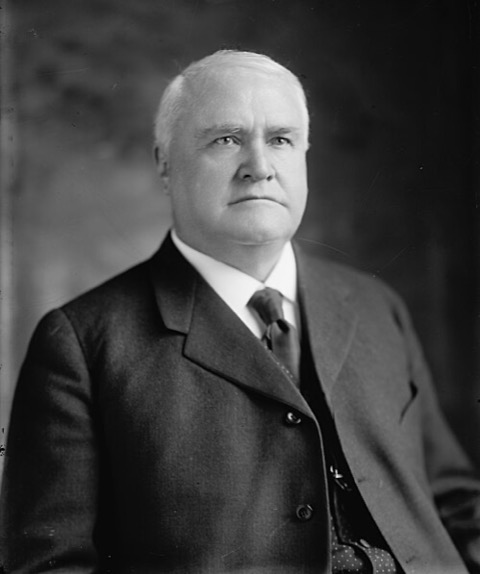

The most prominent among the leaders of the Santa Fe Ring were future U.S. Senator and Secretary of War Stephen Benton Elkins and future U.S. Senator Thomas B. Catron – college roommates at the University of Missouri who fought on opposite sides in the Civil War.

(Stephen B Elkins)

Elkins had served in the Union Army as a captain in the 77th Missouri Infantry. His father and brother joined the Confederates. Stephen twice encountered Quantrill's Rebel Raiders and was spared from being killed because of this family connection. After serving in New Mexico’s government in various capacities from 1867 to 1890 he began developing oil, coal, and timber industries with his father-in-law in West Virginia; served as Secretary of War in the Benjamin Harrison administration (1891-93) and senator from West Virginia (1895-1911.)

Catron instead joined the Confederate forces. He then held a series of judicial and elected government positions in New Mexico beginning in 1867 becoming heavily involved in the effort to gain statehood – and in 1912 was selected by the State Legislature as one of the state's first two U.S. Senators. After leaving office in 1916, he attempted unsuccessfully to receive an appointment as Ambassador to Chile and retired to Santa Fe, dying there in 1921. His biographer Victor Westphall wrote that Catron’s “friends admired his energy and leadership, but his enemies viewed him as a greedy land grabber and ruthless politico.” By 1894 Thomas Catron had become the largest single landowner in New Mexico and perhaps the United States – around 3 million acres.

A recent former Governor has been reported as saying that “corruption in New Mexico isn't a felony, it's a business opportunity.”

Same as it ever was.